In the previous post, we gave you some insights about the simulation of simple birth-death processes with simmer. The extension of such a methodology for more complex queueing networks is immediate and was left as an exercise for the reader.

Similarly, today we are going to explore more features of simmer with a simple Continuous-Time Markov Chain (CTMC) problem as an excuse. CTMCs are more general than birth-death processes (those are special cases of CTMCs) and may push the limits of our simulator. So let’s start.

A gas station has a single pump and no space for vehicles to wait (if a vehicle arrives and the pump is not available, it leaves). Vehicles arrive to the gas station following a Poisson process with a rate of vehicles per minute, of which 75% are cars and 25% are motorcycles. The refuelling time can be modelled with an exponential random variable with mean 8 minutes for cars and 3 minutes for motorcycles, that is, the services rates are

cars and

motorcycles per minute respectively (note that, in this context,

is a rate, not a mean).

This problem is described by the following CTMC:

with . The chain is irreducible and recurrent. To theoretically find the steady state distribution, we have to solve the balance equations

with the constraint

There are independent columns, so the latter constraint is equivalent to substitute any column by ones and match it to one at the other side of the equation, that is:

The solution represents the probability of being at each state in the long-term. Therefore, we can calculate the average number of vehicles in the system by summing these probabilities multiplied by the number of vehicles at each state. In our case,

# Arrival rate

lambda <- 3/20

# Service rate (cars, motorcycles)

mu <- c(1/8, 1/3)

# Probability of car

p <- 0.75

# Theoretical resolution

A <- matrix(c(1, mu[1], 0,

1, -lambda, (1-p)*lambda,

1, mu[2], -mu[2]), byrow=T, ncol=3)

B <- c(1, 0, 0)

P <- solve(t(A), B)

N_average_theor <- sum(P * c(1, 0, 1)) ; N_average_theor## [1] 0.5031056Now, we are going to simulate the system with simmer and verify that it converges to the theoretical solution. There are various options for selecting the model. As a first approach, due to the properties of Poisson processes, we can break down the problem into two trajectories (one for each type of vehicle), which differ in their service time only, and therefore two generators with rates and

.

library(simmer)

set.seed(1234)

option.1 <- function(t) {

car <- create_trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

mcycle <- create_trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=0) %>%

add_generator("car", car, function() rexp(1, p*lambda)) %>%

add_generator("mcycle", mcycle, function() rexp(1, (1-p)*lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}Other arrival processes may not have this property, so we would define a single generator for all kind of vehicles and a single trajectory as follows. In order to distinguish between cars and motorcycles, we could define a branch after seizing the resource to select the proper service time.

option.2 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- create_trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

branch(function() sample(c(1, 2), 1, prob=c(p, 1-p)), continue=c(T, T),

create_trajectory("car") %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])),

create_trajectory("mcycle") %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2]))) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=0) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}But this option adds an unnecessary overhead since there is an additional call to an R function to select the branch, and therefore performance decreases. A much better option is to select the service time directly inside the timeout function.

option.3 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- create_trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() {

if (runif(1) < p) rexp(1, mu[1]) # car

else rexp(1, mu[2]) # mcycle

}) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=0) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}This option.3 is equivalent to option.1 in terms of performance. But, of course, the three of them lead us to the same result. For instance,

gas.station <- option.3(5000)

library(ggplot2)

# Evolution + theoretical value

graph <- plot_resource_usage(gas.station, "pump", items="system")graph + geom_hline(yintercept=N_average_theor)

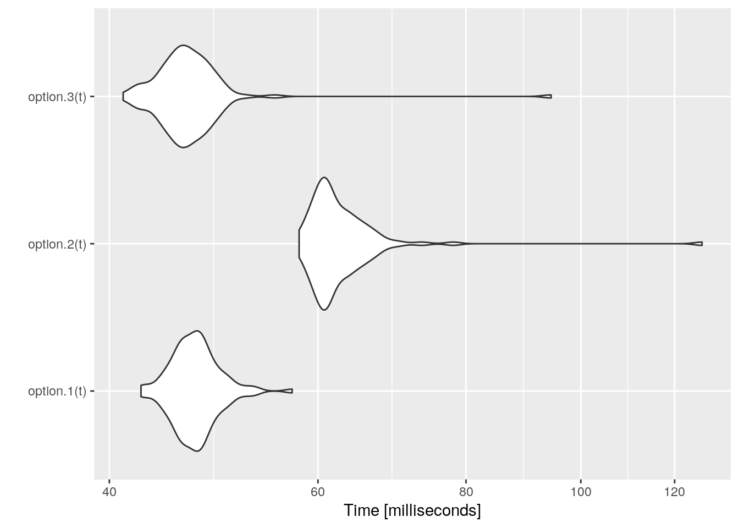

And these are some performance results:

library(microbenchmark)

t <- 1000/lambda

tm <- microbenchmark(option.1(t),

option.2(t),

option.3(t))

graph <- autoplot(tm)

graph + scale_y_log10(breaks=function(limits) pretty(limits, 5)) +

ylab("Time [milliseconds]")